Robert Ashley’s death last week gave me the odd feeling that I should have been listening to more of his music. Absurd really, to self-impose a kind of obligation to consume. The truth is I loved his work but never felt much of a compulsion to listen to the recordings. They seemed beautiful shadows of something genuinely new, something he spoke about, wrote about and enacted: a different way of being within music.

Robert Ashley’s death last week gave me the odd feeling that I should have been listening to more of his music. Absurd really, to self-impose a kind of obligation to consume. The truth is I loved his work but never felt much of a compulsion to listen to the recordings. They seemed beautiful shadows of something genuinely new, something he spoke about, wrote about and enacted: a different way of being within music.

He was one of the few composers of his generation (and subsequent generations) who fully understood that after Cage, electronic music, free jazz, pop music, happenings, proliferating media and all the rest of it, you couldn’t just carry on as if nothing untoward had happened, making your ‘experimental’ music with all the formal constraints and solemn ritual still in place. There’s an interesting essay Ashley wrote for the CD release of Alvin Lucier’s Vespers and other early works (New World Records, 2002). You can’t hear Vespers on a recording, he says, because the experience of hearing the music comes from the space in which it’s performed. He also talks about attempts to subvert the concert hall or redesign concert halls specifically for experimental music, as if it’s going to stand still for another hundred years to please the architects. He talks about fire marshalls. Basically, if you think you’re being subversive but at the same time pleasing the fire marshalls then you’re not subverting much at all.

A lot of composers and musicians shared that sentiment for a while but then turned away into less problematic territory – back to the 19th century or to a vision of jazz bars as they were prior to the 1940s, wherever their spiritual home might be. Robert Ashley worked out ways to make a piece that could be heard on television, or heard in a public space as if you were in a hotel room alone, hearing some other guest’s discarnate mellifluous speech rhythms coming through the adjacent wall and by putting a glass up to the wall and listening hard you could eavesdrop on this man’s muffled monologue about the particles of life, recited to the accompaniment of a radio broadcast by Liberace or one of those early New Age composers from Los Angeles, but Liberace after his audience has departed the building and his secret deepest vision of a cosmic music is finally given a silence in which to float like a voluminous sun bed on a Hollywood pool.

There was a stillness or stasis about Ashley’s pieces that demanded some new venue for listening that just doesn’t exist. In a way, television (arguably the most important medium of the 20th century but a wasteland for almost all composers) was the best way to encounter what he did, a box in which dreams spewed forth as if mind itself; now television is pretty much dead in the aether so there’s a moment that won’t come back.

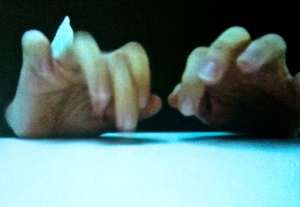

In what setting should music be experienced? The question resurfaced, as it does in every exhibition that demands listening, while I walked around Cevdet Erek’s Alt Üst exhibition at Spike Island in Bristol (15 February to 13 April 2014): the video of his fingers attempting to tap out a sonic translation of a timeline of life-related events; the measures, markers and cycles alluding to sound’s temporality; the rooms called Üst and Alt – day and night, up and down, high and low, heaven and underworld. Blue LED lights and bass beats measure time in the murky claustrophobia of Alt, and in the dazzling sky light of Üst, a cardiac pulse of a low beat emanates from under the feet as if seeping upwards from the underground below. All of the ideas within the exhibition came together in that moment of being within the shock of daylight, the emptiness of a room, sound coming from elsewhere.

In what setting should music be experienced? The question resurfaced, as it does in every exhibition that demands listening, while I walked around Cevdet Erek’s Alt Üst exhibition at Spike Island in Bristol (15 February to 13 April 2014): the video of his fingers attempting to tap out a sonic translation of a timeline of life-related events; the measures, markers and cycles alluding to sound’s temporality; the rooms called Üst and Alt – day and night, up and down, high and low, heaven and underworld. Blue LED lights and bass beats measure time in the murky claustrophobia of Alt, and in the dazzling sky light of Üst, a cardiac pulse of a low beat emanates from under the feet as if seeping upwards from the underground below. All of the ideas within the exhibition came together in that moment of being within the shock of daylight, the emptiness of a room, sound coming from elsewhere.

Later that afternoon (04.03.14), I gave a talk at Spike Island about music and time, playing tracks like Joe Hinton’s “Funny How Time Slips Away”, Sly Stone’s “In Time”, Felix Hess’s frog recordings from Australia, an exceedingly slow, sacred Javanese gamelan from Jogjakarta (“Sekatan Kyahi Guntur Madu”), Arpebu’s “Munsta from Kavain Space” and Ryoko Akama’s “Jiwa Jiwa”, created on the Max Brand synthesiser during a composer-in-residence programme at IMA in Austria. Ryoko’s recent CD – Code of Silence (www.melangeedition.com) – gives no information about the latter piece other than its title so I asked her for some thoughts. Her return email spoke about sine waves and beat frequencies, sustained tones, other worlds with the emptiness of sonic ‘surfaces’ and an aesthetic that arises not from duration but the complexity of listening and its context and conditions.

She translates “Jiwa Jiwa” as “slowly but certainly happening”, giving the example of finding a water leak coming through the ceiling, the stain gradually growing in circumference: “You might say – it is getting jiwajiwa there, water is permeating jiwajiwa.” So the sound is a type of sculpture (maybe like the slower kinetic sculptures of the 1960s by Pol Bury, Gerhard von Graevenitz and David Medalla); change is taking place but at a rate that is hard to discern, closer to stasis than movement.

In the same week (07.03.14) I gave a talk in the Royal College of Art’s Vocal Dischords symposium, using the technique of automatic writing I’d tried once before at Bristol Arnolfini’s Tertulia – Writing Sound event, a set-up in which I write without a script and whatever I write can be seen on screen by the audience in real time. The question of whether automatic writing is possible in these circumstances becomes part of the performance, not least in the sense that fluidity of so-called inner thought is hard to realise except in private. The pace is slower than speech, more stilted or inhibited by observers, subject to error and revision. At one point I played an extract from Robert Ashley’s Automatic Writing and in that heightened, stressful atmosphere heard it as unvoiced thoughts bubbling out of the eyes like soap, seeping slowly from the pores of a face.

For all I know this live performance of writing may be painful to watch but it comes, in part, from an active questioning of spontaneity in improvised performance, along with a questioning of the voice-as-sound, the droning seducer that transmutes ideas into theatre (or so it hopes). What are voices in the head? In pursuit of the origins of spontaneity in 20th century music I have been reading largely forgotten writers who experimented with automatic writing and what William James described as stream-of-consciousness. Mary Butts is one of them, an author whose short and turbulent life included the largely thankless task of assisting Aleister Crowley with the editing of Magick in Theory and Practice. Her novel Armed With Madness (1928) opens with a sentence that makes you want to love it – “In the house, in which they could not afford to live, it was unpleasantly quiet.” A description of listening and silence as uncanny and occult follows, not dissimilar to passages written by Virginia Woolf at almost exactly the same moment in history.

Dorothy Miller Richardson is another. Her Pilgrimage series of 13 novels, the first published in 1915, was a meticulous, if highly selective recording of a life, each instalment given an enticing title, each of which could be the name of a film I would pay to see: The Tunnel, Pointed Roofs, Honeycomb, Deadlock, Revolving Lights, The Trap, Dawn’s Left Hand. The protagonist – Miriam – lives a modest, unspectacular life. In The Tunnel (1919) she is ecstatic to be renting a dingy room that gives her some measure of independence. Time barely seems to move, yet the cycles of life, day and night, the cruel measurement of work and time off, drudgery, disgust and tea, the tasks to be performed at a given time within the patterns of her job, her walks through a London that feels both hostile and magical, the surging and ebbing of feelings, convictions, confidence and often silenced opinion open out, fold upon fold, light and dark as she learns how to live and finally to write. The reader is caught in the streaming of this interior monologue (as Richardson liked to call it), absorbed, like Robert Ashley, in the particles of life: “As she began on her solid slice of bread and butter St. Pancras bells stopped again. In the stillness she could hear the sound of her own munching. She stared at the surface of the table that held her plate and cup. It was like sitting up to the nursery table. ‘How frightfully happy I am,’ she thought with bent head. Happiness streamed along her arms and from her head. St. Pancras bells began playing a hymn tune in single firm beats with intervals between that left each note standing for a moment gently in the air.”

An ordinary life; a dull life even, yet the polyphony of emotions and sensations is hallucinatory in its measured precision and accumulation of bliss: “The lecturing voice was far away, irrelevant and unintelligible. Peace flooded her.” Why do we have to spatialise time, sound and thought, reducing all three to a manageable linearity and locus that has nothing to do with the way we think or hear? Because they are elusive, everywhere and nowhere. The pouring of thoughts, thoughts under thoughts and other inexplicable murmurings of consciousness may take place in a dark room of the imagination within the body as if a kind of ectoplasm gushing out of some hidden spring and dispersing into nothingness, into the blood or becoming a sound recognisable as audible words, the marks of writing or some other signs on or from the body.

I’ve had an idea about Ashley as well. Made the effort to listen to some records. I noticed him having the discipline to sing or speak what he thought. Did you read the book Perfect Lives? I thought it better than the opera… saw that on T.V. long ago and wasn’t impressed. At any rate he had the ability to fuse the extremely public with the super-introspective. I’d like to hear the spanish language version Vidas Perfectos: we don’t hear much spanish here in seattle, perhaps I could learn more of the language that way.

Pingback: come on she said just make like you want me | my nerves are bad to-night