“Rice paper possesses a materiality of emptiness and absence. Its surface does not shine, and it is as soft as silk. When folded, it hardly makes a noise, as if it were stillness itself, condensed in matt white.”

Byung-Chul Han, Absence (2007/2023)

In 1971-2 I had the good fortune to take part in improvisation workshops given by drummer John Stevens at Ealing College. Back then, even though John was challenging some of the fundamental ideas of what music could or should be, we still thought of ourselves as musicians. We all played conventional instruments, working with pitch relationships and temporal agility to create a sound that had historical connections to both Anton Webern and Ornette Coleman. Despite their attachment to the practice of music, John’s exercises led us to a contemplation of sound as a thing in itself; how to think in terms of brevity, sustain, the micro, the extended, the body and its connections. Search and Reflect was the term by which these workshops came to be known. For what did we search? On what should we reflect? Fortunately, that was unclear, something to work out for yourself.

For me, search and reflect opened up to listening, a far more expansive and inclusive practice than music or even sound. The crucial importance of listening is evident in so many aspects of life, mundane and profound. Every day we fail to listen, to really hear (ourselves, fellow human beings or the other-than-human world), and this leads to misunderstandings, bad decisions, conflict and confusion at all levels of being, some of them so catastrophic as to threaten the future of the planet. Improvisation, as John Stevens taught it, is a way to find connections to others, to develop a common language out of difference, and listening is the channel through which we can become open enough to do so.

This key concept – Search and Reflect – has stayed with me as wellspring and centre. For fourteen years I ran improvisation workshops at London College of Communication, always including exercises devised by John Stevens. Outside the university I also developed a form of workshop that listened to objects, foraging for emotional resonance, for echoes of a more complex strand of listening. How was it possible to unlock memories of listening from inside an object? How was it possible to hear messages embedded in silent objects, like paintings or photographs? At the same time I studied Zhan Zhuang chi kung for more than ten years and was struck by the positive effects of its silence and stillness.

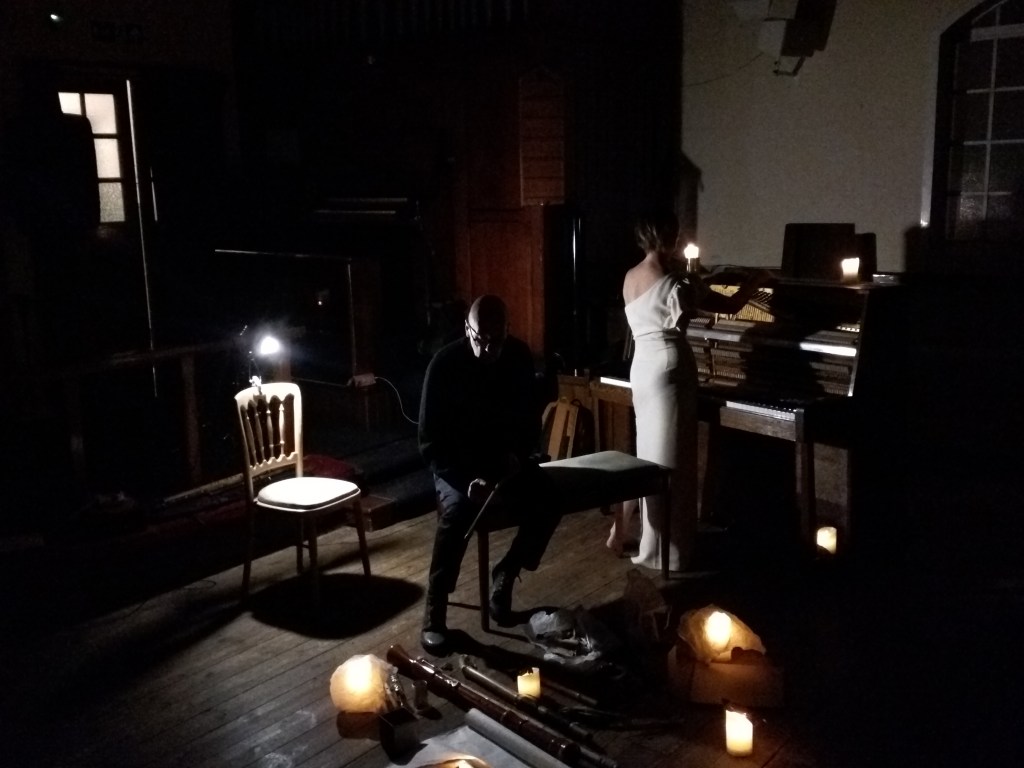

Then in early 2023 I met Ania Psenitsnikova. She had extensive expertise in body work of various kinds and we both had experience with performance art and Butoh dance but identifying with any specific style was not the point. Immediately we began discussing ideas about performance that embraced a wider definition of listening, not just the ear but the whole body attuned to the speaking of the world. How was it possible to enter a space and leave no trace, we asked ourselves? Sound, yes, but sound is frequently a pollutant. Our duo performances under the name of Moreskinsound became an intensive examination of how collaborative listening (in its expanded sense) – through microsound, stillness, slowness, silence, non-intentional movement, materials, objects, light and shadow – intensifies and sensitizes our sense of self in relation to the phenomenal world.

Having run workshops together this summer/autumn, in Prague, Kristiansand, Tokyo, Kunisaki Peninsula and Fukuoka, we are now preparing for the first in a series of London-based workshops entitled Soundbody. Scheduled for February 2026, this workshop is an intensive exploration of how sound and movement can expand our sense of self. Through improvisation with sound and movement, in particular the voice, participants can release emotional blocks, reduce inhibitions, and deepen awareness of space, body, and different states of presence.

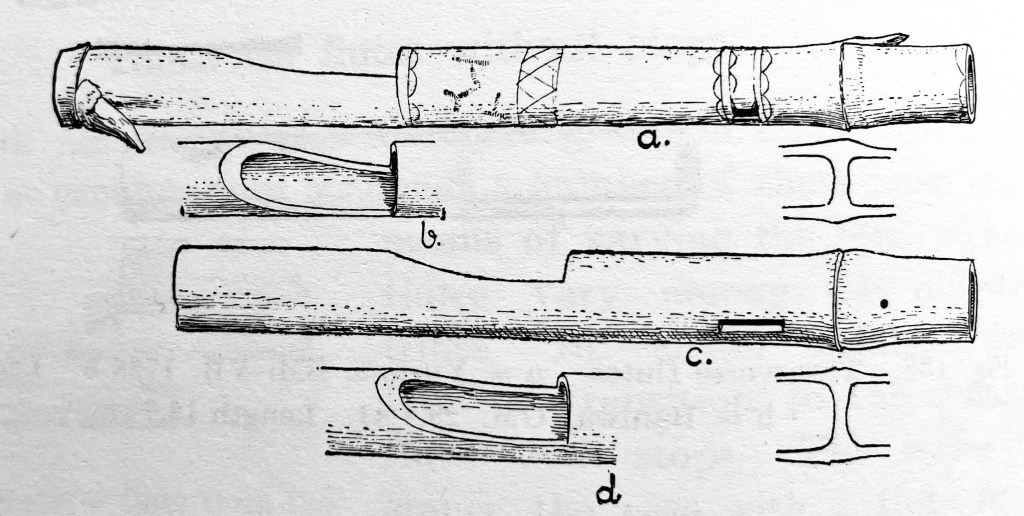

Soundbody is a resonant, listening being, investigating its inner and external spaces, experimenting with sensory potential, physicality, and stillness. We will explore silence, micro-sound, stillness and non-intentional movement as ways to expand listening capacity, leading to an ecological approach to being in space. The first step is to listen intensively to unfamiliar sound worlds, extending beyond hearing through the ears to the whole body. The body becomes a complex ear, attuning to the auditory life of objects, materials, and non-human entities.

Through exercises in movement, attention, awareness, breathing, inner listening, and sound improvisation, we will develop a listening that deepens experience of spatial awareness, our own bodies, emotional memory and each other. To prepare both body and perception, we will begin with exercises designed to enhance flexibility, strength, endurance, and responsiveness. Developing awareness and perception is also a key focus of this workshop.

Location: Studio Ma, London, E1 4BG.

Dates: Saturday 21st/Sunday 22nd February, 2026.

Time: 12.00 – 18.00 (doors open 11.30)

No previous experience or background in dance or music is necessary.

Early Bird Special: book now to secure your spot at a discounted rate.

DM me for more details.

Surprise is a dubious pleasure, cultivated in the search for musical forms that take the listener into realms of impossible/imaginary. Then suddenly, after decades of searching, the surprises diminish in quantity, often in quality, leaving an unavoidable sense of melancholy, mixed with the treacherous air of nostalgia.

Surprise is a dubious pleasure, cultivated in the search for musical forms that take the listener into realms of impossible/imaginary. Then suddenly, after decades of searching, the surprises diminish in quantity, often in quality, leaving an unavoidable sense of melancholy, mixed with the treacherous air of nostalgia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.