and so it was the blues falling upon us . . . like a lot of other people, my head was burning and turning from the reality of an American president in 2017 unwilling after Charlottesville to fully distance himself from neo-Nazis, white supremacists, the KKK and other racists and so it was that I learned of Paul Oliver’s death. My copy of The Meaning of the Blues was close to hand and so it was I came to read Richard Wright’s forward, the conclusion of which said this: “The American environment which produced the blues is still with us, though we all labour to render it progressively smaller. The total elimination of that area might take longer than we now suspect, hence it is well that we examine the meaning of the blues while they are still falling upon us.” This was written in 1959, in Paris, for a soon-to-be architectural historian, English and art school trained, who had fallen in love with the blues and produced a book that was to contribute greatly to the scholarship and spread of a subject almost entirely outside his direct personal experience.

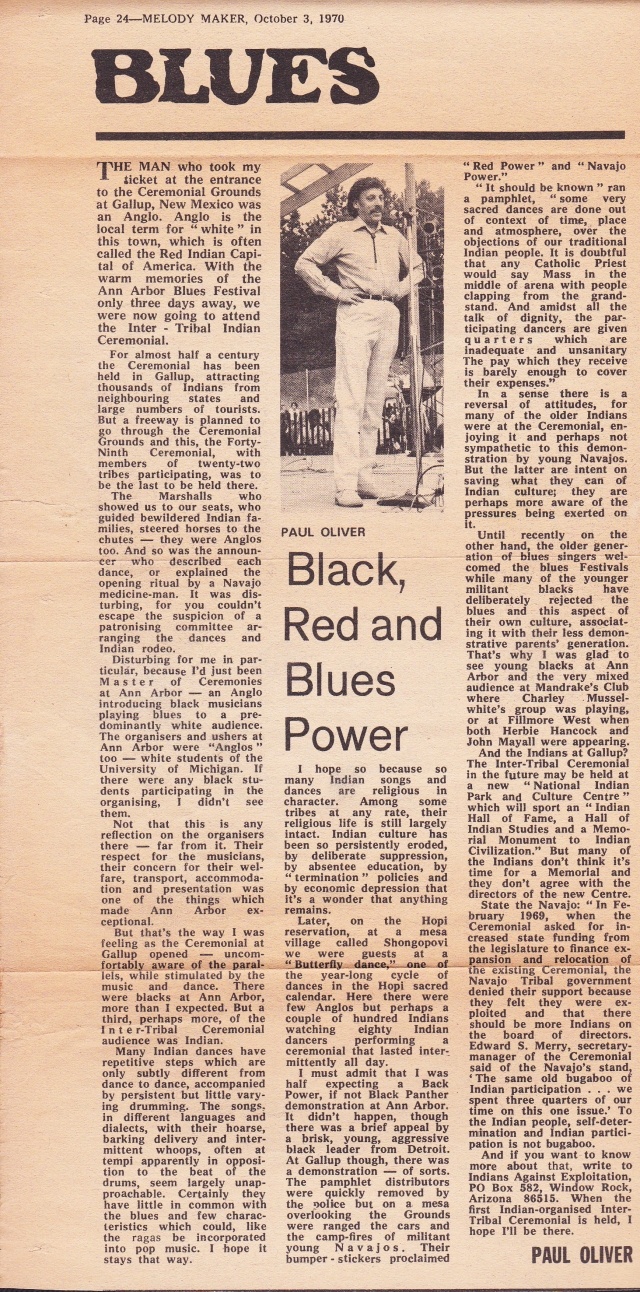

I was a teenager, maybe fifteen, when I read The Meaning of the Blues (in other editions titled Blues Fell This Morning). Oliver’s manuscript was finished in 1958, finally published in 1960 by which time he was on the road in America, recording interviews with an extraordinary range of blues singers, Speckled Red to Little Walter (recovering from a bullet wound), Mary Johnson to Sweet Emma Barrett. Oliver’s writing taught me how to think about music, make connections through to history, context and politics, particularly race politics; how to make some sense of an obscure lyric. In 1967, when I read Conversation With the Blues, the fruits of that field trip to a black America still enduring Jim Crow laws in the south, I began to develop an understanding of how to transcribe the cadence of vivid speech patterns, how to write about the relationship of music to its practitioners, their circumstances and the society of which they are a part.

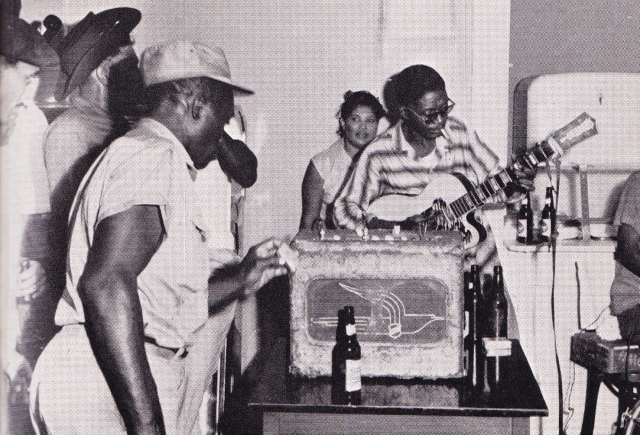

Lightnin’ Hopkins at the Sputnik Bar, Houston (photo by Paul Oliver)

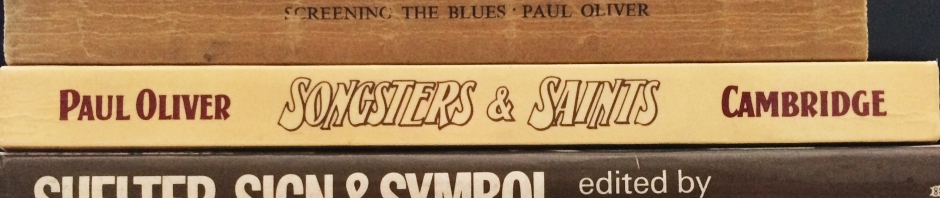

What I didn’t learn from him was how to write about the sound of the music. That seemed outside his purview, except for some isolated examples in Savannah Syncopators where intense encounters – “[in Ghana] . . . a chorus of women sings in chanting fashion, with one woman leading with vocal lines to which they respond, seemingly without relationship to the compelling rhythms of the adowa band . . .” – demanded description as evidence in a search for answers to questions about African retentions in the blues. How well his answers hold up after 37 years is for somebody else to decide but this approach inspired me when I wrote Rap Attack.

The exoticism of blues to a person like me, growing up in the suburban periphery of London in the 1950s and 60s, was one of the subjects I addressed in Exotica in 1999. After a trip to New York where I’d met Charles Keil, a fascinatingly perplexing track by J.B. Lenoir – “I Sing Um the Way I Feel” – had been on my mind. “Paul Oliver, one of the most eloquent of blues scholars,” I wrote, “had visited Lenoir in 1960, recording their conversation on a heavy EMI tape recorder that disintegrated when he journeyed south into the humid summer heat. Lenoir talked to him about dreams: the dreams of an old devil. ‘somethin’ with a bukka tail and the shape of a bull but he could talk’, that made his father quit singing the blues; a dream his mother had sent him, giving him numbers for the lottery; the musical inspiration that came to him, ‘like through a dream, as I be sittin’ down, or while I be sleepin’’.”

In 1984, Oliver prefaced the collected essays of Blues Off the Record with some cautious autobiographical notes that shed light on his obsession with the blues. As a teenager in 1942 he did ‘harvest camp’ in Suffolk, farm work taken on by teenagers to replace agricultural labourers called up for military service in World War II. Americans were building a base in Stoke-by-Clare, and Oliver’s friend Stan persuaded him to eavesdrop on a gang of black soldiers digging a trench. After a while most of the GIs were marched away, leaving two alone to finish the job. “We stayed behind the hedge,” Oliver wrote, “getting cold. I was getting impatient too, when suddenly the air seemed split by the most eerie sounds. The two men were singing, swooping, undulating, unintelligible words, and the back of my neck tingled. ‘They’re singing a blues,’ Stan hissed at me. It was the strangest, most compelling singing I’d ever heard . . .”

Oliver’s influence, though not his acuity and depth of knowledge, is plainly evident in the first review I ever wrote, 600 or so words about a Realm LP – Dirty House Blues by Lightnin’ Hopkins – published in a self-produced school magazine called ONE, circa 1965 or 66. Much of it was cribbed from the LP sleevenotes and where my own opinions surface they are embarrassingly naïve. I was searching for something, comparing “Everything Happens To Me” to James Brown’s version of “Why Does Everything Happen To Me” without knowing anything about the convoluted origins of that song (and I still don’t know much), also finding “affinities, strangely enough” between a Hopkins solo on “Long Way From Texas” to the “fast clusters of bent, cascading notes” played by Otis Rush, Magic Sam and Buddy Guy. Strangely enough I don’t hear those affinities quite so clearly now. What we hear is determined by what we search for.

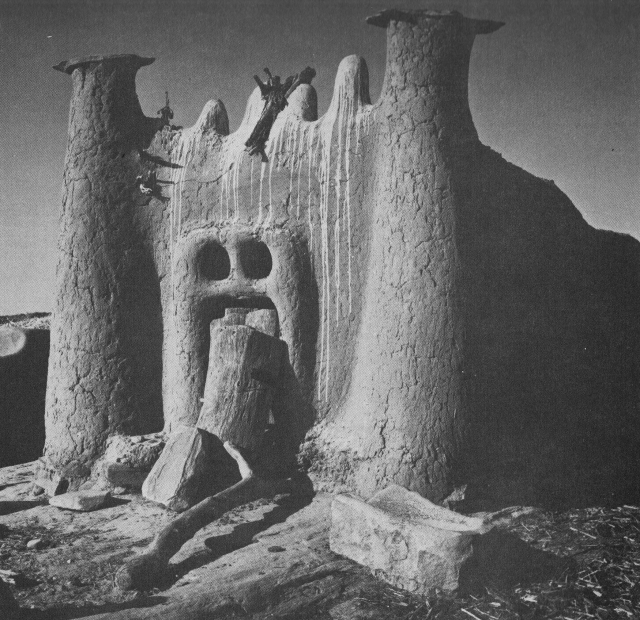

Dogon ancestral shrine (photo Corrie Bevington)

Oliver’s main job lay in architecture, specifically vernacular architecture and the symbolic significance of shelter. In other words he was interested in structure and those symbols, rituals and beliefs that “identify, seek or invest meaning” (as he wrote in his introduction to Shelter, Sign & Symbol, published in 1975). This may be why (excepting the example above) he kept himself and his subjective responses to the sound of blues out of his music writing. But he was acutely conscious of the problematic aspects of a white man from Britain writing so extensively about African-American culture and was prescient in 1966, if somewhat mistaken, to think that the music’s future was bleak.

The circumstances of his death are unknown to me but presumably he was unaware of the weekend’s violence in Charlottesville and its continuing repercussions. If he had been able to follow these events, I imagine he would have felt profound sympathy with Black Lives Matter, since that was the motivational force that led him to write about African American life through its music, back in 1951 when he was exasperated by the attention given to jazz at the expense of gospel and blues. And knowing of a US president recklessly tweeting threats of fire and fury he might have dreamed himself back at the beginning of his book publishing career, to the violence unleashed upon Freedom Rides, and to the Cuban Missile Crisis, which threatened to kill us all. As Richard Wright said, this may take longer than we think, and so it was the blues falling upon us.

A very deep thanks for this.

Thank you Mike – familiar territory for you.

Dear David

Delightful as always and I never knew that Paul Oliver was English even though I bought “The Meaning

Of The Blues” in the early Sixties.

Blues records were hard to buy in Australia at that time and that book gave me a lot of records to send for

overseas.

It really did give me some idea of the meaning of the blues.

I am 71 now and still love that music and still get a thrill when the needle drops down on Howlin’ Wolf,

Robert Johnson, Memphis Minnie, Blind Lemon Jefferson and all the other great singers and players

I learnt about in Paul’s books.

RIP to a great man and one who changed the world for the so much better.

Regards

David N. Pepperell

Melbourne, Australia

Thank you David.