Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit.

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit.

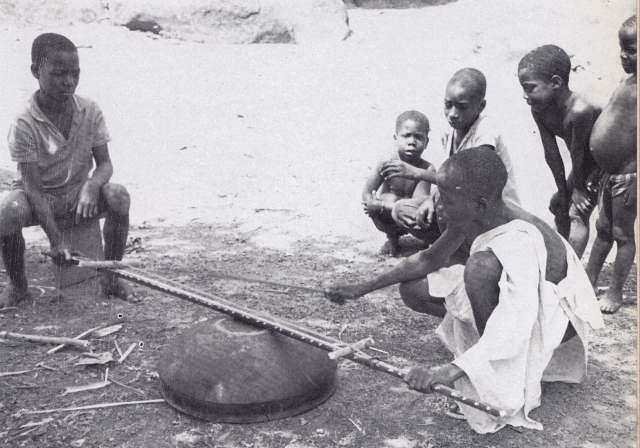

Coincidence because of a social media discussion about the Ocora record called Musiques Dan, recorded in Côte d’Ivoire by Hugo Zemp in 1965 and 1967. Was there an example of an instrument using a hole in the ground for resonance? There are many extraordinary sounds and sound-making devices on that record – whirled slit aerophone, bullroarer, mirlitons, metal basin, the ground struck by big sticks, sieves filled with bronze jewellery, enamel basins filled with gravel, water drum, stone whistles – but maybe the strangest is Mask-that-eats-water, a pit dug into the earth and covered by bark. Fixed into the bark are vegetable fibres that are rubbed by two players. For reasons not entirely clear to me though perhaps explained by the ‘slip and stick’ theory whereby water affects dynamic and static friction at a very fast rate, water is poured onto the fibres by a third player, hence the name of the mask.

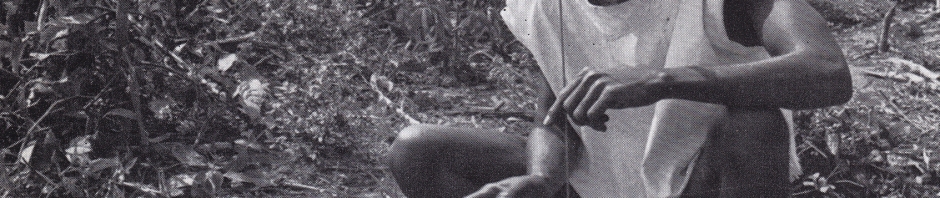

A photograph of a different earth instrument appears in Zemp’s book: Musique Dan: La musique dans la pensée et la vie sociale d’une societé africaine (1971). This one is equally ingenious but more elaborate, more conventional. In a chapter entitled Mythes d’origine des instruments de musique, Zemp gives what his informant tells him is the origin of the Arc-en-terre (my translation): “The bow in the ground belonged to an unfortunate, a little unfortunate. This boy had nothing with which to amuse himself; he could neither play the harp-lute, nor beat the drum, nor blow into the trumpet. Then he dug a hole in the ground, covered it with leaves, fixed a vegetal fibre there, and attached the other end to a branch which he buried in the ground. When he struck the rope, it spoke grrrrr grrrr. He says, It’s enough for me to amuse myself. This boy was an unhappy person. It is for this reason that the earthen bow remains with the children. It is not a thing to distract important people, it is for the unhappy.”

One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.”

One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.”

The reference almost certainly came from French musicologist André Schaeffner’s Origine des Instruments de Musique (1936). In Art, ethnography and the life of objects (2007) Julia Kelly situates such ethnographic objects within the operations of circumstantial magic, as she puts it, “. . . at the boundary between the animate and the inanimate . . .” traversed by French surrealists in the late 1920s and early 1930s. She quotes Schaeffner’s argument, that ethnographers should study musical instruments falling outside recognised categories, for example “the most humble wooden box used to produce sound.” An extreme example from many points of view, not least museology, was a pit dug in the ground. “Schaeffner was also concerned with the least conservable of musical instruments,” Kelly writes, referring to an article on musical instruments from the Trocadéro’s ethnographic collections, “an Abyssinian ‘earth drum’ consisting of two holes in the ground of differing heights. This instrument could only be captured photographically, and indeed was virtually illegible in the dark photograph by [Marcel] Griaule published alongside the article, where only the player’s hands and arms gave any indication of its existence.”

The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

from New/Rediscovered Musical Instruments (1974)

As Morton makes clear, discussions such as the one I am having now and have been having for nearly fifty years, became taboo, either because they were damned for cultural appropriation, primitivism and exoticism or dismissed for being hippyish, lacking in the detachment and rigour proper to a person who was considered to be permanantly Severed. But ultimately these holes in the ground address a basic problem – how to make a small thing bigger – and by applying the principle of resonance they fashion an elegant solution whose imprint will gradually soften and crumble into an impression rather than a scar. We could learn something from that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.