Recently I’ve been watching YouTube clips of Max Wall performing in his role as Professor Wallofski – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEU8Hr4nqV8. The weirdness of antiquity hangs over this kind of comedy but unlike other entertainers of the Music Hall era, Wall’s influence (on John Cleese and Les Dawson, for example) is clear and his abject yet distasteful persona, tattered creature of the night who has fallen into the wrong world, is compulsively creepy. Part of his professorial status is earned through a piano whose presence requires not only music but a configuration of the body. Wall’s arachnid body malfunctions under the pressure of this demand (not uncommon among virtuosi); his wrists go floppy or one arm becomes shorter than the other, must be extended and then compared in a routine that addresses the piano as a near-silent phantom of cultural rectitude, patient and implacable in its search for the perfect human specimen.

Recently I’ve been watching YouTube clips of Max Wall performing in his role as Professor Wallofski – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEU8Hr4nqV8. The weirdness of antiquity hangs over this kind of comedy but unlike other entertainers of the Music Hall era, Wall’s influence (on John Cleese and Les Dawson, for example) is clear and his abject yet distasteful persona, tattered creature of the night who has fallen into the wrong world, is compulsively creepy. Part of his professorial status is earned through a piano whose presence requires not only music but a configuration of the body. Wall’s arachnid body malfunctions under the pressure of this demand (not uncommon among virtuosi); his wrists go floppy or one arm becomes shorter than the other, must be extended and then compared in a routine that addresses the piano as a near-silent phantom of cultural rectitude, patient and implacable in its search for the perfect human specimen.

All musical instruments come with baggage. In fact they are baggage – objects of surrealist furniture that speak. Smash them, burn them, build them in funny shapes or digital simulacra and yet they grin back: “still here”. Seeing Rhodri Davies set himself up to play amplified harp at Café Oto last night reminded me of Max Wall, not because Rhodri gurns, suffers limb rubberisation or wears black tights but because the instrument is the ventriloquist doll that has the last word. Whatever you do to me tonight, I am the harp of your childhood and all childhoods, it says. Now do your worst.

The enactment of that drama is gripping. He picks up a wooden harp, a sharp triangle small enough to be cradled on the lap like a miniature dog, and before a note is sounded I’m reminded of something else, a little book once published by the British Museum: Ancient Musical Instruments of Western Asia. The cover showed a photograph of a reconstructed silver lyre from the Royal Graves of Ur, found in what is called the ‘Great Death Pit’ and dated c. 2600-2400 BC. Lyres and harps, flutes, rattles, bells and scrapers were ritual instruments in ancient Mesopotamian civilisation. Something similar was true for Japan, Korea and China. We can read about this in Arthur Waley’s translations of The Nine Songs, Chinese wu (shaman) songs from before the fourth or third century BC: “The zithern-strings are tightened; drum answers drum. The bells are beaten till the bell-stand rocks. Sound of flute, blowing of the reed organ; a clever and beautiful spirit-guardian.” In Nara, Japan, housed in Todaji Temple’s Shosoin collection, is an eighth century triangular harp called a kugo. According to Toshi Ichiyanagi, who reconstructed the instrument for his Ancient Resonance project, there is an image of an angel holding a kugo in Buddhist murals within the cave temples of Dunhuang in Western China (also the site where the Diamond Sutra of 868, the world’s oldest surviving dated printed book, had been hidden for centuries until discovered by a late 19th century Taoist monk called Wang Yuanlu).

Like the wood inside the silver casing of the Ur lyre, all of this venerable history and ritual significance decomposed to dust during the ruthless 20th century prettification and trivialisation of harps, flutes and bells. Is it too far fetched to imagine some bonus-swollen investment banker keeping a harpist chained to a radiator below stairs on permanent call for dinner parties? Probably not, but it’s one job that Rhodri won’t be offered any time soon. Just switching on the amp set fire to that particular model of civilisation – the unleashed hum was enough to trigger anxiety attacks in any sound engineers and audiophiles present. Maybe it comes as shock, hearing a musician more closely associated with quietism and minimalism playing in this way. He strikes the strings hard, repeating arpeggios over and over, restricting himself to one area of the harp; stopping, then resuming with a close variant in another area. The playing is expert but rough, as if he is pushing himself to play at the edge of error, rather than training himself (as he must have done in the past) to play cleanly and precisely. After a while he wipes sweat from his head. This is effort, though not for me as a listener.

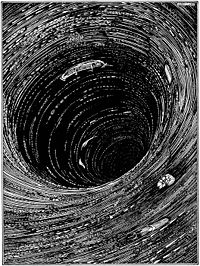

As a strategy it sounds unusual in the context of music which follows a long symphonic arc (true for a lot of so-called experimental music that I hear out and about). There’s no attempt to resolve anything, to ease in like a cat or conclude with a chocolate or a firework. Each piece is a cell, a version of what came before and what will come after; they begin, they stop. Mostly he plays with distortion, sometimes extreme, and when the strings seem to tumble over each other like church bells in a Bosch nightmare then I think of the green-cowled harpist creature mounted on a screeching primeval monster in The Temptations of Saint Anthony.

Listening to his new vinyl, Wound Response (www.altvinyl.com) a few days before this gig made me think of a tradition that has nothing to do with the sort of music you might hear at that other Boschian nightmare, the Classical Brit Awards. Immediately I heard echoes of Konono No 1 or the Kasai Allstars from Kinshasa, the donso ngoni hunter’s harp from Mali and Guinea, the Ethiopian begena recorded by Ragnar Johnson, the harps and lyres recorded by Hugh Tracey in southern and eastern Africa, the nyatiti harp recorded by David Fanshawe in Kenya, the inanga trough zither recorded in Burundi by Michel Vuylsteke. The latter is famous for its whispered vocal, to our ears sinister but apparently pitched to cut through the frequency range of the strings. There were no whispered vocals forthcoming at Café Oto though Ragnar Johnson’s recording of a song of the Monophysite Church of Ethiopia, accompanied by the deep buzzing of the begena, the harp of David, might have been appropriate since the words dwell on the transitory nature of life on earth: “It will eat you, and even the earth will eat you, like an ignorant man, like a man easily deceived.”

I also thought of another record that arrived in the same week as Wound Response, the freshly remastered CD issue of King Crimson’s Larks’ Tongues in Aspic. Jamie Muir’s involvement in this version of the band was big news in 1972 and although the extreme physicality of Jamie’s performances are absent on the recording, there are glimmers of what might have been. Most exciting to me was the opening of the title track, a very African influenced introduction that suggested a new approach to the interaction of instruments and rhythms in rock music. Whatever the potential, there was always a song or a crunching onslaught of power riffs to blow it aside. I can imagine that Rhodri might have been asked to join the band on the strength of his new direction, were this 1972, and probably lasting as short a time as Jamie Muir.

But in the end this is not just about the hegemony of the harp of politeness or about formal directions in music. It’s about a prevailing mood. “The Theatre of Cruelty will choose themes and subjects corresponding to the agitation and unrest of our times,” wrote Antonin Artaud in 1933. Rhodri quotes Kazimir Malevich on the cover of his record: “and may the freed bear bathe his body amid the flow of the frozen north and not languish in the aquarium of distilled water in the academic garden.”

On my way home from Café Oto I was forced to walk for the last part of the journey. A car was on fire in a side street, smoke pouring from its already blackened body. Somehow it seemed a fitting end to the evening.

You must be logged in to post a comment.