The late-19th century spiritualist and campaigner Louisa Lowe was unjustly, if legally, incarcerated because her husband claimed she was mad. Giving evidence against her, the proprietor of Brislington asylum – Dr Charles Henry Fox – had this to say: “She writes these revelations on leaves of trees, or any dirty scraps of paper she may casually find, and she liberally distributes them.” There is something immediately familiar about this image of visions and so-called ‘passive writing’ (automatic writing, we might say) inscribed on leaves; maybe we should all be imprisoned for similar madness. As in the cases of spiritually inspired artworks by Hilma af Klint, Georgiana Houghton and Emma Kunz, it raises serious questions about the gender bias of art history and the progenitive nature of a canon that disallows rule breaking anomalies, because they are of the wrong type, have the wrong motivations, come from the wrong place or simply lack a particular style of self-awareness deemed indispensible to modernism.

All this is easier (if not straightforward) to dispute when there are extraordinary artworks to contemplate. Louisa Lowe’s leaves and scraps are lost to an ineffable history of fragile and impermanent materials, along with those auditory manifestations of spiritualism that were so important to its efficacy as a spectacle of loss and empowerment. As scholars such as Alex Owen and Anne Braude have argued, spiritualism was a vital channel through which women, their voices otherwise suppressed, could ‘speak’ and establish agency, yet we have no documentation of what a séance sounded like, with its sonorous theatre of knockings and tappings, bells ringing and tambourines rustling in the dark, instruments played with no apparent human intervention and disembodied voices. According to Alex Owen in The Darkened Room, spirit writing would appear spontaneously on blank sheets of paper, “nobody actually witnessing its production but all able to hear the movement of pen on paper.”

Georgiana Houghton, Glory Be To God, 5th July 1864

Spiritualism – hearing and transmitting messages from an invisible, largely unknowable spirit world – was a listening practice with a radical proposal: that the field of listening extends beyond what Karen Barad calls (in Meeting the Universe Halfway) “. . . a container model of space and a Euclidean geometric imaginary.” In my experience this sensation of moving through extended listening fields is fairly common during improvised music performance. At Hundred Years Gallery last September, a Sunday afternoon quartet of Douglas Benford, Sylvia Hallett, Billy Steiger and myself, I was experimenting with bone conduction speakers, attaching them to small objects – a rusty cowbell, a small metal container for gramophone needles bought in Porto Alegre, books that have some significance in my long struggle to better understand listening and resonance – in order to amplify voices and archival musics to a level of ghostliness that matched their place in memory.

During a duo with Sylvia Hallett in the first half, she and I became aware of unidentifiable sounds, like another music, that was growing from within our soundfield but appearing to come from elsewhere. Neither of us found this surprising. Sylvia often uses a microphone and looping to sample and reconfigure real time playing; I was playing field recordings, interviews with subjects like Ornette Coleman and a cassette tape of Chinese religious processional music that I had copied in the early 1970s from BBC Sound Archive recordings, through my osophonic set-up. The potential for ambiguity was considerable, made more so when I learned that Sylvia’s microphone wasn’t in use. This was mystifying, though not particularly abnormal.

In the break, Douglas picked up a phone message to say that his father had been taken ill, though things were not so bad that he should leave immediately. In the second half I played a duo with Billy Steiger. At one point Billy went upstairs into the café. In the basement we could hear his footsteps crossing the ceiling, stomping around, hear his violin faintly, as if from another world. Back downstairs his violin was picked up and distorted by one of my vibration speakers, placed on a small tambourine on the floor to amplify the sound but suddenly acting as a receiver. All of these crossings between instruments, sources, materials, histories and places made it somehow irrelevant to maintain any identification with a sound or its point of origin. In the final quartet I felt the impulse to hold a bone conduction speaker to my skull. The music playing through the speaker came through clearly to me, like an inner voice, though I was aware that nobody else in the room could hear it. Differences between inside/outside, here/there, then/now seemed, not exactly to melt away, but to open up tiny glimpses into a radically changed sense of the world.

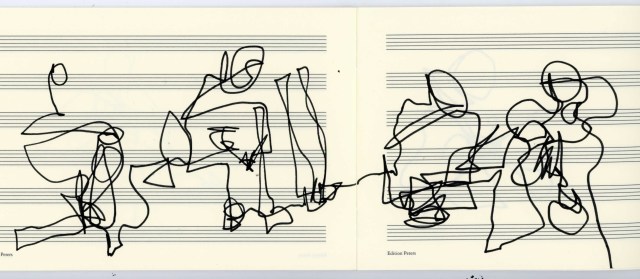

Calum Storrie, Hundred Years Gallery, 18 September 2016

Later that evening, Douglas sent an email. “Sounds like we were playing when my dad passed away at home,” he wrote. “It was very sudden and painless they think . . . to be honest he went the way he would have wanted.” The following day he sent links to a recording of the music, along with drawings of our various groupings by Calum Storrie, each one made in a continuous line, the drawing instrument not leaving the page until the end of the line. I felt a compulsion to write about this event; so many thoughts and emotions rising out of it. As I wrote to Douglas at the time, seeking his permission: “It’s a gig we will all remember because of the circumstances . . . It’s a question of what recordings can’t absorb or retain, in this case a major life event that escapes the microphone entirely and yet the music sounds more dramatic, less ghostly than it did in the room, so perhaps our memory of the event is somehow imprinted despite the technical impossibility.”

As it transpired I was unable to write, maybe because so many other implications were crowding out this more prosaic theme of recording and its limitations. Even now, the raw materials refuse to coalesce, swirling around each other like one of Georgiana Houghton’s spirit drawings.

Pingback: David Toop’s ‘Raw Materials’. | likeahammerinthesink