Nine people sitting on the basement floor folding paper into origami birds, four microphones hanging from the ceiling, a loudspeaker pair at each end of the room. A sound going on, unmistakeably but ambiguously emanating from this activity, suggestive of the palpitations of a locust swarm, the feeding of insect eaters biting their way through a bounty of desiccated wings and bleached bones. The white cranes accumulate, piling up in earthbound flocks next to their makers. I am conscious of furniture in the room, the chair on which I sit, the movement of hands, a thin garment hanging loosely on the wall, a vivid red teapot.

Nine people sitting on the basement floor folding paper into origami birds, four microphones hanging from the ceiling, a loudspeaker pair at each end of the room. A sound going on, unmistakeably but ambiguously emanating from this activity, suggestive of the palpitations of a locust swarm, the feeding of insect eaters biting their way through a bounty of desiccated wings and bleached bones. The white cranes accumulate, piling up in earthbound flocks next to their makers. I am conscious of furniture in the room, the chair on which I sit, the movement of hands, a thin garment hanging loosely on the wall, a vivid red teapot.

Gradually, patterns emerge in the sound, lulls falling mysteriously, overtaken by industrious surges. A Max patch is at work. Now the sound piece thins, leaving a sparse acoustic crackle that exactly matches the quick, concentrated effort of the folders. Their number has grown to fourteen. This is a durational piece – four hours at this point – so some of them have returned from a break. The atmosphere of dedication is the focal point that holds it all within its shape and volition, no obvious breakage points other than the sight of doing and making, the growth of birds.

Gradually, patterns emerge in the sound, lulls falling mysteriously, overtaken by industrious surges. A Max patch is at work. Now the sound piece thins, leaving a sparse acoustic crackle that exactly matches the quick, concentrated effort of the folders. Their number has grown to fourteen. This is a durational piece – four hours at this point – so some of them have returned from a break. The atmosphere of dedication is the focal point that holds it all within its shape and volition, no obvious breakage points other than the sight of doing and making, the growth of birds.

Upstairs we speak in low voices, respectful of the crackling quiet below.

For a moment I think of Chim-Pom’s installation pieces – Non-Burnable, Real Thousand Cranes and The History of Human – all of which refer to the vast quantities of paper cranes sent from all over the world to the city of Hiroshima each year and to the practice of Senbazuru, folding one thousand paper cranes connected together by strings. According to Japanese legend, a person who folds one thousand paper cranes – one for every year of the mystical crane’s life – will be granted whatever they wish for.

But then I think of the sounds of labour: the physical impact of an axe cutting into a tree, the making of objects by hand, a typing pool (as seen only in old films) or the agricultural workers in Suffolk who would ease the monotony of threshing by mimicking the patterns of bell-ringing, their flails beating the same rhythm on the elm floor as the bells in a church steeple.

There are those records in my collection devoted only to songs and sounds of working: a Folkways 10-inch LP, The World of Man: His Work, which, notwithstanding the title, includes examples of women working: a Norwegian woman calling cattle to the barn to be milked, a Japanese woman spinning thread, women waulking, pounding and pulling tweed in the Hebrides, singing to make the work go with joy and pace. Then more grim than that, Alan Lomax’s recordings of prison songs made at Parchman State Penitentiary, Mississippi, in 1947, and Bruce Jackson’s Wake Up Dead Man: Black Convict Work Songs from Texas Prisons, made in 1965-6, the percussive thud of axes and hammers resounding in hot air as they rise and fall in unison, beating the rhythm of songs like “Rosie”, “Grizzly Bear” and “Early In the Morning.”

Lucie Stepankova’s idea for Fold was to bring together a spatial composition with this physicality, the working of paper and legend, “[exploring] the sonority of the ancient tradition of paper folding (origami), its ritual aspects and meditative potential. It values collectivity, simplicity and the transcendental quality of repetition over a long duration.”

Lucie Stepankova’s idea for Fold was to bring together a spatial composition with this physicality, the working of paper and legend, “[exploring] the sonority of the ancient tradition of paper folding (origami), its ritual aspects and meditative potential. It values collectivity, simplicity and the transcendental quality of repetition over a long duration.”

At the beginning of Yasunari Kawabata’s post-war novel, Thousand Cranes, a young woman serves tea to the male protagonist. She becomes known as the girl of the thousand cranes, simply because she “carried a bundle wrapped in a kerchief, the thousand-crane pattern in white on a pink crape background.” The image of a thousand cranes haunts the text. Starting up in flight or flying across the evening sun, their flashes of brilliance momentarily cut across guilt and suffering. “The sound of her broom became the sound of a broom sweeping the contents from his skull, and her cloth polishing the veranda a cloth rubbing at his skull.” Happiness is a wish.

Fold, a listening environment, was performed at Hundred Years Gallery, E2 8JD, during the afternoon of Saturday March 24th, 2018.

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit.

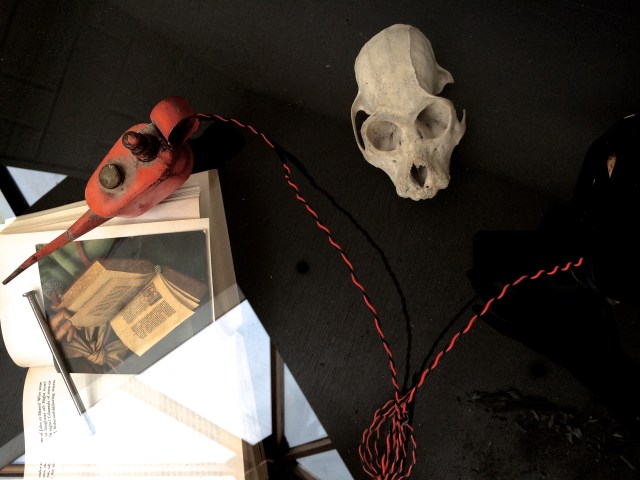

Maybe a coincidence but during our Sharpen Your Needles event last night (28.09.17) Evan Parker played “Music for Mbale (Ndokpa)”, from The Photographs of Charles Duvelle: Disques Ocora and Collection Prophet, a sumptuous book and two CDs published by Sublime Frequencies. Recorded by Duvelle in Ngouli, Central African Republic, in 1962, the instrument played by two men for the Mbale village festival was a lingassio, a four key xylophone mounted over a pit. One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.”

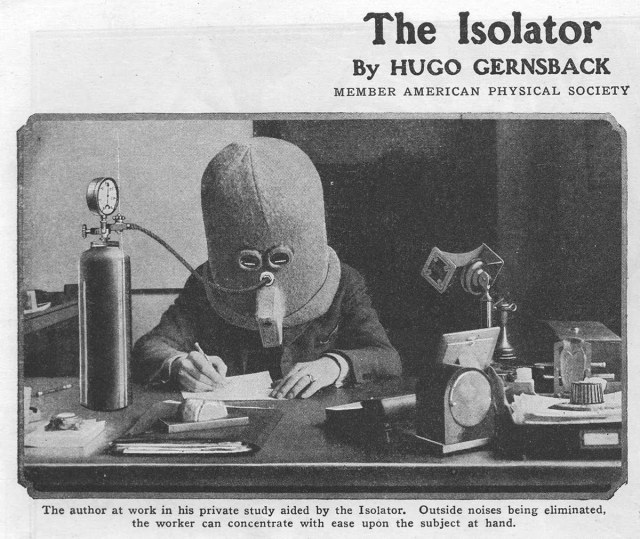

One lesson to be learned from this is not to jump to easy conclusions about earth instruments and primitivism. The Dan had other ways of amplifying sound, as the above photograph shows, but terra-technology floated somewhere out on the edges of society, either marginal, in the sense of being a diversion for the melancholy and immature, or spectral, as sound masks emitting the voice of a supernatural being. When I was beginning to research non-western music in the early 1970s unilinear cultural evolutionism was still prevalent. To find any subtlety in the literature you had to read ethnomusicologists like Klaus P. Wachsmann (father of improvising violinist Philipp Wachsmann). In my early twenties I was excited to read his chapter – The Primitive Musical Instruments – in Musical Instruments Through the Ages (edited by Anthony Baines, 1961). “While considering them,” he wrote, “it must be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a musical instrument can only be measured by the degree of satisfaction its sound gives to the people who use it.” He devotes a short section to what he called Ground Instruments: ground zithers, percussion beams, stamping pits, ground bows and, most fascinating of all: “In Abyssinia a narrow, tapering hole is made in the ground and howled into; the vernacular name of this instrument means ‘lion’s call’.” The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

The allure of such an instrument, hole within a hole, absence within absence, Is out of all proportion to its simplicity. One contribution to the above mentioned social media thread came from Ilan Volkov, who drew my attention to Christian Wolff’s Pit Music (1971), published in Prose Collection. The piece could easily be a description of how to make your own version of the Dan earth bow, though that seems unlikely as both Zemp’s book and Wolff’s composition emerged in the same year. As Ilan pointed out, Wolff never intended his Pit to be actually made. Like a lot of things, post-Fluxus, it was an indication of potential (political as much as anything) rather than an imperative. I wrote similarly provisional pieces a few years later, the Wasp Flute that was never put into practice even though the instrument was built, and hypothetical events in which I performed with seals and fish, all of them suggestions of how life might be lived in a world less traumatised by what Timothy Morton has called The Severing (in his new book, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People).

While eating shojin ryori cuisine outdoors at Izusen, Daitokuji temple, Kyoto, in spring sunshine, April past, I reflected on François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness, the appreciation of blandness or insipidity in ancient Chinese aesthetics and ritual practices. Commenting on a text describing the use of muted music during ritual offerings to the ancestors he says this: “For the most beautiful music – the music that affects us most profoundly – does not . . . consist of the fullest possible exploitation of all the different tones. The most intensive sound is not the most intense: by overwhelming our senses, by manifesting itself exclusively and fully as a sensual phenomenon, sound delivered to its fullest extent leaves us nothing to look forward to. Our very being thus finds itself filled to the brim. In contrast, the least fully rendered sounds are the most promising, in that they have not been fully expressed, externalized, by the instrument in question, whether zither string or voice.

While eating shojin ryori cuisine outdoors at Izusen, Daitokuji temple, Kyoto, in spring sunshine, April past, I reflected on François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness, the appreciation of blandness or insipidity in ancient Chinese aesthetics and ritual practices. Commenting on a text describing the use of muted music during ritual offerings to the ancestors he says this: “For the most beautiful music – the music that affects us most profoundly – does not . . . consist of the fullest possible exploitation of all the different tones. The most intensive sound is not the most intense: by overwhelming our senses, by manifesting itself exclusively and fully as a sensual phenomenon, sound delivered to its fullest extent leaves us nothing to look forward to. Our very being thus finds itself filled to the brim. In contrast, the least fully rendered sounds are the most promising, in that they have not been fully expressed, externalized, by the instrument in question, whether zither string or voice.

You must be logged in to post a comment.